polyworking: why one job isn't enough anymore

2024 was the year of doing everything at once for me. I jiggled a full-time job as an engineer, teaching data science and AI engineering, mentoring, some consulting gigs, attempts at building my own product, a bit of writing.

It was exhausting. Also kind of addictive.

There's definitely a point where it became overwhelming. I learned that the hard way. But the question isn't whether to avoid multiple interests, but it's how to navigate them sustainably.

what is polyworking?

There used to be this website called Polywork. It was sort of a LinkedIn alternative where instead of pretending you're just a "AnyTitle at SomeCompany", you were encouraged to share diverse skills, collaborate and own a layered identity: for example, you could be a designer who also teaches salsa, makes cupcakes and volunteers at local school. Some call it hustle culture or side gigs, but apparently there is a term for that: polyworking.

Unfortunately they couldn't make a business case: they tried to pivot to AI-powered personal websites in 2024 (of course), but the core - championing multi-faceted professionals - got lost and eventually they shut down. But the concept stuck with me: why settle for one routine when modern life (and tech) allows us to build several?

This question of multiple identities made me think about how we typically introduce ourselves to others.

you are not your linkedin headline

"Tell me about yourself."

Ask someone this question and chances you will get a job title. "I'm a software engineer." "I'm a financial analyst." As if your identity could be captured in a LinkedIn headline.

Even worse is when people define themselves by their employer. "I work at Microsoft/Google" becomes shorthand for who they are. I find that limiting, even a little sad. People are more than their job.

But this wasn't always the case.

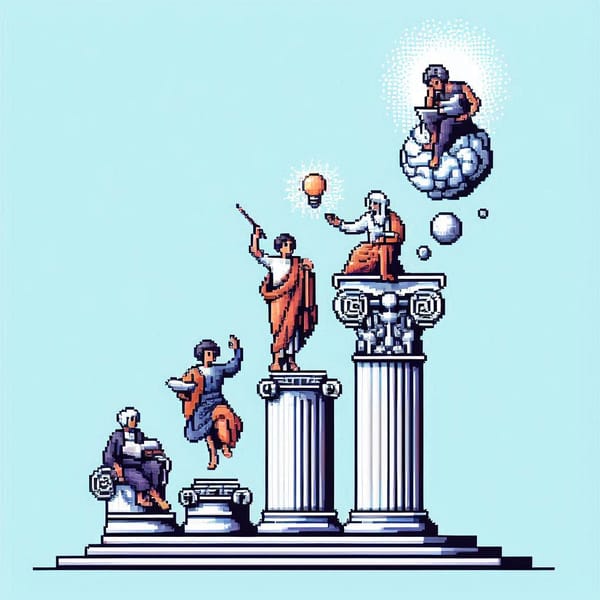

leonardo didn't pick a lane

I read a lot of biographies and historical books and I noticed something: the people we remember rarely did just one thing. Einstein worked at a patent office while revolutionizing physics. Leonardo da Vinci didn't choose between art and engineering - he did both, plus anatomy, plus architecture. Benjamin Franklin was a printer-inventor-diplomat-scientist. Even closer to our time, Steve Jobs blended technology with liberal arts. The pattern repeats: the people who shape culture tend to operate across boundaries.

The ancient Greeks had a word for this: paideia. The cultivation of a complete human being through gymnastics, rhetoric, music, mathematics, and philosophy.

They weren't training specialists. They were developing humans. And humans were never designed to be a single-threaded.

Somewhere along the way - probably during industrialization - we decided that being well-rounded was inefficient. Better to train people to do one thing exceptionally well. You operate this machine. You write this type of code. You analyze these specific numbers.

It made us replaceable, which was the point.

I went to schools where STEM was priority over social and humanities subjects. The typical school curriculum in Kazakhstan usually contains languages, literature, history, and geography. You were supposed to have breadth of knowledge, but back then I believed this to be a waste of time and energy. I loved spending a lot of time doing Math and sometimes was lagging in other subjects and, luckily for me (or not really?), in the schools I attended this was encouraged behavior. Math mattered the most, because engineers seemed to matter the most, right?

Now with some maturity in life and kids starting local school here in Spain, I changed my mind. I like this concept of well-roundedness. I love that public school is going to teach Arts to my 6-year-old son.

Because why do we pretend humans are meant to do one thing?

the infrastructure for curiosity

My kids will probably have jobs that don't exist yet. My current job didn't exist five years ago. So how can someone study something at college and prepare for a job that doesn't exist yet? The whole idea of picking one track and staying specialist (or better said, a person with just one skill or expertise) doesn't seem like a future-proof option.

We spent decades forcing people to specialize, and now AI comes along and makes specialization kind of pointless. As someone using and building AI tools at my day job, I see firsthand how it is changing this dynamic.

Few questions to think about:

- Is polyworking the future way of working in the AI-first world, where everyone does freelance or project-based work?

- Will AI help us become well-rounded so that we can develop expertise in many areas quickly? Kind of like a "10x engineer" - who can do data science, data engineering, AI engineering, front-end, back-end – one person who can do everything with AI?

The current reality though is that the infrastructure for polyworking is much better now. Remote work means I can teach in Kazakhstan while living in Spain. AI tools mean I can be competent enough in adjacent domains without years of study. Platforms exist for every type of work - teaching, consulting, building - which means you can experiment without committing.

But also: companies are starting to expect it. Startups want engineers who can do product thinking and designers who can vibe-code prototypes. Enterprises want consultants who actually built things. Students want teachers who work in industry.

back to being human

I don't think everyone needs to become a polyworker. Some people genuinely love going deep on one thing, and that's beautiful. But for those who've always felt constrained by single-track careers, who see connections everywhere, who get energized by variety rather than exhausted by it - this might be the moment.

Most of us have probably felt this tension between what we're "supposed" to focus on and what actually interests us. It's curious how we've normalized this limitation.

What we need to change is the mindset. Stop asking "what do you do?" and start asking "what are you curious about?" Stop defining ourselves by job titles and start embracing the full spectrum of what we can contribute.

Because in the end, we're not software engineers or data scientists or teachers. We're humans who happen to write code, analyze data, and share knowledge.

And humans, it turns out, have always been polyworkers.